Opinion

-

Official Temperature Data Aren’t ‘Data’ and Shouldn’t Be Used to Restrict Freedom

Opinion -While the surface data may be the best source we have, when it is as biased or even fabricated as it is increasingly found to be, there is no way it should be used to drive public policies limiting the freedom of billions of people in their personal and economic affairs, all in the vain hope of controlling the weather in the future. -

Governments Cannot Change the Automobile Market

Opinion -What went wrong for electric vehicles a century ago were the same things that hold consumers back today. -

Florida’s New ‘History of Communism’ Law Is a Model All States Should Follow

Opinion -I spent five years teaching U.S. history, world history, and American government, during which I chronically witnessed what I can only describe as “socialist indoctrination” from most of my colleagues. In many cases, blatantly pro-socialist ideology was being masqueraded as “giving both sides.” -

Is Widespread Illegal Voting the New Normal?

Opinion -One of the reasons that I believe more voters than ever are prone to engage in illegal voting is because the federal government wields vast powers, far beyond what the Founding Fathers envisioned when they drafted the Constitution. -

New Poll: Nearly Three in 10 Voters Say They Would Vote Illegally in 2024 Election

Opinion -The best course of action to achieve robust election integrity is for state lawmakers to impose sound election rules that prevent the possibility of illegal voting from occurring in the first place. -

Innovating for a Water-starved Planet

Opinion -Perhaps instead of spending countless trillion of dollars trying to replace fossil fuels with wind, solar and battery technologies, we should focus on adapting to whatever climates we live in or encounter -- especially since China is building hundreds of coal-fired power plants to manufacture wind turbines, solar panels, EVs, grid-scale batteries and transformers to sell to Western nations for that “energy transition.” -

Heartland Institute Poll Shows Nearly Three in 10 Voters Would Vote Illegally in 2024 Presidential Election

Opinion -Press Release -According to the poll, conducted by Rasmussen, approximately 44 million Americans would vote illegally in 2024 election “to prevent other side from winning.” -

-

California Sets New Rule for Chevron, Gas Price Is Expected to Rise

Opinion -In a recent interview, energy expert Ronald Stein discussed California’s shifting energy landscape and the challenges of transitioning away from fossil fuels. -

Off Shore Wind Farms Are Detrimental to Whales

Opinion -Although correlation does not automatically lead to causation, in this particular instance, it sure seems likely that there is a connection between the rapid rise in whale deaths and the pre-construction and construction activities of the off shore wind farms along the U.S. East Coast. -

Lack of Consumer Demand for Electric Vehicles Must Be Acknowledged

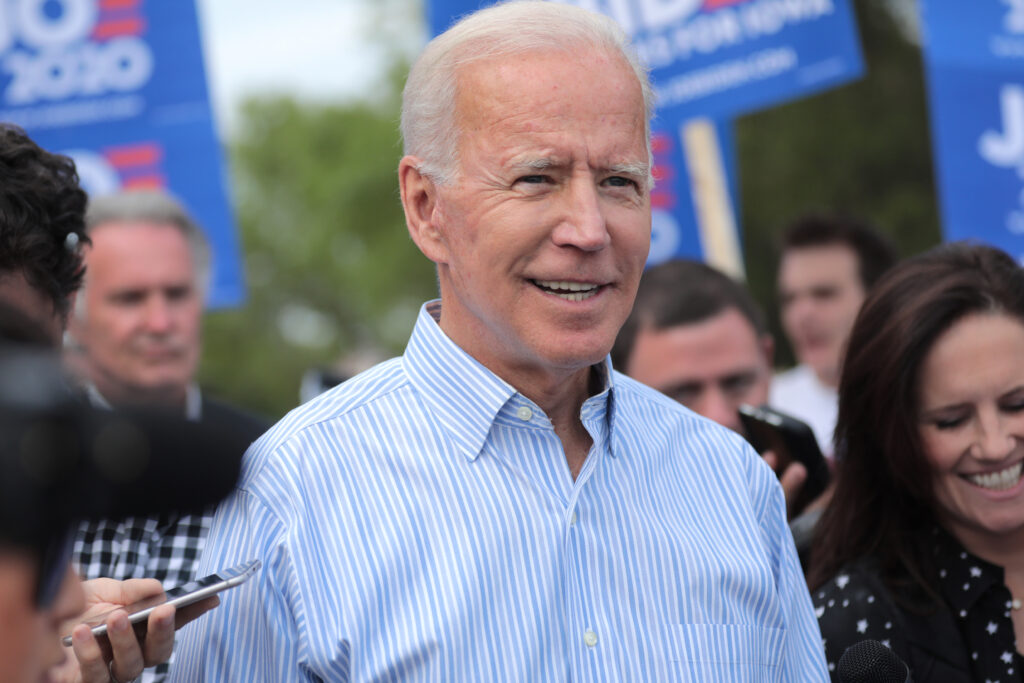

Opinion -Because the lack of organic consumer demand for EVs is becoming more apparent by the day, the Biden administration is resorting to heavy-handed tactics to “nudge” Americans away from gasoline-powered cars. -

Biden’s Medicare Advantage Cuts Are Tantamount to Throwing Grandma Over the Cliff

Opinion -Biden didn’t merely propose Medicare Advantage (MA) reforms a dozen years in the future. He cut rates from a projected 2.44 percent to 2.33 percent, despite industry predictions of a 4 to 6 percent growth rate. -

PRESS RELEASE: Whales Die While Dominion Energy Hides Crucial Information

Opinion -Press Release -Federal regulations prohibit even one human-caused death per year if the right whale is to survive as a species. -

Socialism at a Glance

Opinion -The reason that so many American students have a distorted view of socialism is simple: they have been spoon-fed a sugar-coated version of socialism on social media, in classrooms, and throughout the entertainment universe. -

The Age of Underpopulation Is Here

Opinion -The lesson from the overpopulation debacle is that people adapt to their environment. -

Students Deserve to Know the Truth About Socialism

Opinion -For the past few decades, American students have been taught a whitewashed version of socialism. -

PRESS RELEASE: The Heartland Institute Releases New Book: Socialism At A Glance

Opinion -Press Release -Book includes brief history of socialism, breakdown of socialist ideology, several national case studies, and examination of democratic socialism in the United States. -

Heartland’s ‘Climate at a Glance’ is the antidote to Earth Hour

Opinion -So, go to the Google Play Store or Apple App Store and quickly download the “Climate at a Glance” app to your cell phone. -

From ‘The Great Reset’ to ‘The Great Taking’

Opinion -The Great Taking refers to a decades-long plan by a cast of characters hellbent on ensuring that the entire economic game is rigged so much in their favor that they win under practically any and all circumstances. -

As Federal Government Collapses, States Offer Solutions

Opinion -Under the doctrines of unbridled federal and judicial supremacy, the U.S. government has taken on so much power that it can no longer perform its basic functions, let alone do all that it has promised. -

Cyberattacks Against Health Care Industry Are Cause for Concern

Opinion -Cyberattacks like the one perpetuated against UHG are alarming because they could potentially destabilize the entire U.S. health care industry. -

Crying Crocodile Tears Over ‘Sue-and-Settle’

Opinion -Letting outside groups sue the government to compel enforcement actions dates from the Nixon years, and during the Reagan era became a favorite tactic of the environmental industry. -

Gold Hill School: A Symbol of Freedom in Colorado

Opinion -When schools, such as the Gold Hill school, deliver quality education at a reasonable cost, citizens support them. -

Renewables Will Return America’s Lifestyle Back to the Pre-1800’s – This Is the Biden Energy Plan.

Opinion -Germany, the first country to go “green” with an electricity generation transition to renewables, now has electricity rates that are among the highest in the world, and threatens to be an unaffordable, unrealizable disaster, according to the government's own independent auditors.